The Torajan people on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi are a rarity among traditional cultures. They possess something capable of holding at bay the inexorable encroachment of modernity. Something within their cultural essence whose preservation is of great value to the ravenous economic sensibilities of the modern world. Something allowing them to maintain those native customs, ideals and forms so delicately assembled and maintained over countless generations. This commodity is neither land nor material resource but rather a unique and dramatic set of spiritual perspectives and behaviors. The Torajan are a new breed of entrepreneur. In concert with the Indonesian government, they have parlayed their traditional animist practices into big business.

Sulawesi. What on the planet could be more exotic? A remote orchid shaped coral island on the edge of the earth layered in dense tropical vegetation; steeped in a foggy reputation of barbarous pirates, royal kingdoms, head hunting cannibals and animist death cults. Its name and location seethe intriguing yet cautious imagery; Sulawesi, north of Bali, east of Sumatra, west of New Guinea, on the edge of Borneo. The imagination fills with visions of a solitary paradise where glancing breezes and vaguely profiled palms under a waning moon mask a deeper darkness of the human soul. For the contemporary seeker straining to stay ahead of the inevitable spread of Western modernity it seemed a rare opportunity. But one would have to hurry.

Formerly known as the Celebes, Sulawesi first came to the world’s attention as the abode of the dreaded Bugi pirates, whose fearsome prows with their distinctive black, triangular sails launched from the legendary port of Makassar on the southwest coast. The scourge of the 16th century spice trade, the predatory and rapacious Bugi continued to threaten these seas until modern times. However, for those brave enough to test the island’s mountainous interior lay the greater fear; the Toraja. Reputedly a savage and marauding people, the Toraja terrorized other tribes with their ritualistic collecting of human heads and cannibalizing or enslaving their defeated foes. They were thought to practice bizarre death rites uniformly feared and shrouded in macabre mystery. Though twentieth century Dutch colonizers and missionaries had made significant inroads into the Torajan’s business of butchering and eating their neighbors, little had changed with respect to their cultural emphasis on death and the bloody ceremonial practices dominating their society. Comprehensive ethnographic field work on Torajan death rituals had only begun in the mid 1970’s. These studies opened the door to global interest in this reclusive group. Many felt this new found exposure may signal the eventual exploitation and dilution of one of the world’s last authentic tribal death cults. For a time geographical isolation and poor infrastructure kept the Toraja apart from significant numbers of visitors. However, in the early 1980’s the government of Indonesia declared their intention of turning tourism into a lynchpin of national economic revival. Heretofore inaccessible locals such as Sumatra, Borneo and Sulawesi were marked to lead the pack as new destinations of interest.

The Toraja live in a series of villages in an upland area of the island known as TanaToraja just outside the town of Rontepao. The topography and landscape of their surroundings is spectacular. Everything is green. All vistas, aspects and dimensions seemed infused with a hyper saturated lushness of overwhelming, perpetual, infinite green. Profuse, verdant growth ripples over craggy, low lying mountains that cut the sky with their irregular profiles and clings tenaciously to the plunging walls of the rutted valleys whose darkened bottoms are the only break in this emerald monotony. It’s difficult to fathom how early colonizers made their way through the tangled, ceaseless jungle to eventually tame the reclusive Toraja.

The Torajan are not an ethnically distinct people. In point of fact, they’re no different from the Bugi, Makassarese or other proto-Malayan groups who initially populated the island. Toraja was a distinction given to those who lived in the highland areas. Actually the name Toraja is a derogatory word of Bugi origin meaning “up-landers.” It carries all the attendant negative connotations reserved for such appellations as “back woods” or “hillbillies” within American lexicon. Tana Toraja, meaning “area of the up-landers” is an arbitrary administrative and political district cobbled together by the Indonesian government. Though local mythology claims the Toraja a distinct ethnic group who came to the island from the skies by way of a celestial ladder or alternately sailing their large canoe shaped boats from Kampuchea, many heretofore Bugis and Makassarese became Torajan simply by changing locale.

Historically Torajan society was hierarchically structured with three classes of people; nobles, commoners and slaves. Membership in any of these groups is primarily reckoned through descent, though wealth and occupation are beginning to factor into the mix. The nobility consider themselves the continuing lineage of the original heavenly Torajan kings called the manurum. Their earthly positions were subsequently reinforced through greater wealth and the ability to consolidate military power in a highly conflicted region. Those of the nobility accord themselves better housing, food, possessions and spiritual access than those of the lesser classes. Commoners were usually newer, unaffiliated arrivals without any defining bloodlines or wealth, while the slave caste was composed of captured rivals, their affines and those who traditionally served the needs of the nobility. These social divisions were originally created and sustained by the conditions and demands of traditional tribal life. As with many early Indonesians, life in the mountains of Sulawesi was initially fraught with inter tribal warfare and its attendant ritualistic practices of head hunting and cannibalism. Tribal consolidation through conquest brought the expected results; rank and wealth to the victors, suffering and servitude to the losers. Though marauding warfare no longer exists, the initial social divisions these conflicts wrought still endure, though the ownership of slaves is now illegal.

The most intriguing element of Torajan culture is their cosmological world view known as Aluk To Dolo, (meaning “belief of the old.) Aluk To Dolo, or Aluk is most prominently manifested in unique forms of ancestor worship heavily steeped in funerary rituals and animist religious practices. Like so many others, the Torajan believe the cosmos to be divided into three distinct realms; the upper world, the world of man and an underworld. All of these realms are filled with a seemingly endless array of gods or otherworldly creatures. The most prominent deities are Puang Matua ,the god of heaven known as the “old lord,” Pong Banggai di Rante, the god of the earth known as the “master of the plains” and Pong Tulak Padang in whose hands the world actually resides. These three deities work in concert to maintain the equilibrium between heaven and earth and generally oversee the daily affairs of Torajan life. Though the earth itself is devoid of gods it is nonetheless teeming with elements of the supernatural. Every worldly form is thought to be occupied by spirits and ghosts. Trees, stones, mountains and rivers are just some of the places where these lesser, though highly active presences dwell. Then of course there is the underworld. True to universal form the Torajan underworld can be a fearful place occupied by such creatures as batitong, (malevolent spirits who feed on the stomachs of the sleeping,) paragosi, (the Sulawesian equivalent of a werewolf,) and other devious creatures devoted to tormenting human existence and threatening the cosmic harmony.

To man falls the duty of helping the gods maintain a balance between the upper and lower worlds through a series of ceremonies and observances. Almost all elements of daily life have a ritualistic dimension. It should be noted not all Torajan people remain true to their animist roots. So thorough were the Protestant Dutch missionaries that today approximately 80% of Torajan people are now Christian. As the realities of the modern world provide numerous reasons for the survival of Christianity in the highlands, the practice of Aluk has seen certain modifications. Despite this theological shift, traditional material and ceremonial manifestations of Aluk still thrive within the region and attract the increasing hordes of visitors now flocking into the islands interior. I was fortunate. The first time I visited the Torajan was in 1986. At this time the tourist business was in its infancy but changes were underway.

A row of tongkonan with traditionally thatched roofs face northward in the village of Tandung. Stacked horns on the left indicate the great social status of the inhabitants

In 1986 just getting to Rontapeo from the former capital city of Makassar, now called Ujung Pandang, was a grueling, treacherous drive. Once in Tana Toraja travel was much worse. Most roads through the area were little more than mud choked tracks. Despite the persistent sweltering heat and encroaching vegetation walking was the most expedient way of visiting the local villages. Being the closest to town, the village of Kete Kesu was my first stop. From a half mile away I could see the rows of saddleback roofs topping the Torajan longhouses known as tongkonan. Traditionally covered in thick thatch, these long sweeping arcs create the most distinctive and repetitive shape in all of Tana Toraja. Under the ascending gables of the tongkonan are carved intricate, repetitive patterns of traditional Torajan symbols and forms. These geometric mosaics integrate a variety of motifs such as buffalo, cockerels, the sun and a host of other spiritual forms. They are usually painted in four colors: black symbolizing death, white for flesh and bones, red for life and yellow for the gods. The floors of the houses are elevated high off the ground by a series of thick wooden piers. One enters the rectangular interior by use of a long wooden ladder. The houses of the Toraja are always aligned in northward facing parallel rows. North is the revered direction from which legend claims the first ancestors arrived. The front of the tongkonan is customarily adorned with a carved buffalo head and a series of actual buffalo horns ascending the forward support pole. The buffalo is a prominent symbol of Torajan status and the traditional basis of wealth and currency. The more horns displayed, the more wealthy and important the family within. Across from each longhouse sits a smaller replica of the tongkonan used as a rice barn. The open area between the houses and the barns forms the central communal and ritual area of the village. Building a tongkonan is an expensive proposition. Traditionally only noble families could afford them. Commoners reside in more modest, smaller versions of the longhouse and slaves were customarily consigned to shacks or huts.

Though at first glance Kete Kesu appeared consistent with the construction and layout of a classic Torajan village, something was distinctively amiss. The area had a neatness and order most uncommon to rural third world communities whose residents rarely have time for tidy appearances. There was a pristine, manicured quality present that seemed artificial and unsettling. While the entire countryside was currently a muddy quagmire, the grounds of this village were unerringly level and coated with an even layer of perfectly raked black and white pea gravel. There were primly maintained flower beds set behind smoothly grouted stones and the paint on the decorative carvings of the tongkonan showed not the slightest evidence of fading or weathering. Those few people present were all dressed in immaculately cleaned and pressed clothing with not so much as a singular loose thread or displaced button. The distinct lack of animals was also puzzling. Not a pig, buffalo, dog or rooster in sight.

I was too late. Kete Kesu was in the midst of transforming into a “model” Torajan community for the tourist set. I had inadvertently stumbled into examples of these “ethnically preserved” displays in Java and Bali. As I understood the arrangement, government funds are used to restore and maintain selective villages and to pay the residents to act as a form of living history. It’s a curious accord to be sure; villagers are employed, the upkeep is free, tourists are amused, the government makes money and traditional culture is, (in a fashion,) preserved. I quickly encountered an “official” who in perfect English gave me the low down. “I will show you the inside of one of the houses where you will be able to see native craftsman at work and perhaps purchase a souvenir for your friends and family,” he said. “And please do not forget to sign the village guest book before you go. We need to know who our visitors are and where they come from.” Finding the concept of model villages antithetical to my interest, I politely took my leave.

Geometrically incised decorations cover the entire front and gable sections of a traditional tongkonan. The carved buffalo head is a very typical representation found on most Torajan longhouses

I slogged my way a couple of miles down the road to the village of Lemo. Here things appeared a bit more promising. With their splintered side walls and peeling paint the village tongkonan appeared quite authentic and devoid of commercial influence. The adjacent terraced fields were filled with wet rice farmers hard at work and those I met wore worn and tattered T-shirts, jogging shorts and rubber flip-flops on their feet. Not traditional Torajan clothing to be sure, but accurate in its representation of the state of contemporary Torajan existence-poor but unaffected by Western romantic notions. Dozens of unteathered buffalo wandered about.

The buffalo was, and to a large extent remains the cornerstone of Torajan material and social life. For centuries these giant beasts have been the major source of protein in the Torajan diet, the prevailing form of currency, the most conspicuous affirmation of individual status, the method by which inter-tribal cooperation with all its attendant benefits has been established and an object of profound mythological significance.

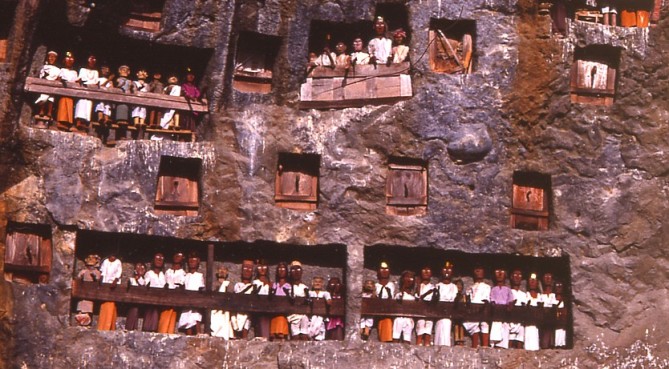

Perhaps the most exciting sight was the presence of funerary effigies, known as tau tau on stone balconies carved into the high cliff faces surrounding the village. The Torajan concept of death and their funeral rites are some of the most distinctive in the world and the predominant fascination of travelers and anthropologists alike. It could accurately be stated that death is the focal point of most Torajan life with the funerary ritual or rambu soloq being the most spectacular element of traditional practice.

A long row of buffalo horns on the front of the tongkonan testify to the wealth of the family who live within. All were most likely funerary sacrifices to the most recently deceased of the household

The elements of the rambu soloq are designed to honor the spirit of the deceased as they transition into the role of an ancestor. However, there is more at work than just according the proper amount of affection and respect due a departed loved one. Keeping one’s ancestors happy and sated is of critical importance. A contented ancestor will guide and protect the surviving members of their family and provide good luck and fortune along the way. Ancestors have but one main requirement to remain happy; wealth, and lots of it. A wealthy ancestor is a contented ancestor. When one goes to the afterlife they are thought to exist for eternity in a material manner similar to the one they had in earthly life. Upon death, it is incumbent on the surviving family members to transfer the worldly wealth of the deceased to an otherworldly locale known as Puya. Puya is the Torajan afterworld or land of the soul. Puya is curiously said to be situated under the earth in a southwest direction. As wealth among the Toraja is traditionally measured in buffalo, this transfer is accomplished by slaughtering as many of these poor creatures as the family can afford through the rambu soloq and sending their essences straight to Puya.

When a Torajan dies they are first wrapped in cloth and placed in a corner inside the family’s tongkonan. There it remains until an appropriate amount of buffalo can be assembled to form a sufficient display of wealth for the deceased. Only then is the funeral held. Sometimes it can take years to assemble an adequate amount of buffalo. During this time the deceased is referred to as “being sick” by the other family members who continue to live alongside the corpse. As Torajan funerals are used to convey status upon the deceased and their surviving kin it is not uncommon for families to spend a preponderance of their lives accumulating buffalo for the eventuality of their own demise.

Having secured a proper number of buffalo, the funeral ceremony begins. Depending on the amount of buffalo to be killed a funeral can last anywhere from a day to several weeks. Funerals of the wealthy or those of high status can attract thousands of people from all over the land and involve the slaughter of hundreds of buffalo. The flesh from the butchered animals is subsequently given to the revelers for consumption while the horns are saved for future display. During the festivities, the dead body is placed inside the family internment area. This is usually a deep vault chiseled high into the faces of the surrounding cliffs or sometimes a nearby cave. Here the body is safe from robbers, as often valuables such as jewelry or gold are interred with the dead. Outside the tomb a platform or balcony is cut into the cliff. A life sized wooden effigy, (or tau tau,) of the deceased is then placed to represent their spirit. Most balconies are filled with numerous tau tau representing complete ancestral lines. Tau tau are commonly dressed in traditional clothing that wears and disintegrates over the years. If the funerary ritual is properly executed and the dead have been found worthy by Pong Lalondong, they will leave Puya and ascend a mountain to heaven. Once in heaven the deceased acquires the status of a revered ancestor and joins in the responsibility of guarding mankind and the ever valuable rice. The death of children necessitates different arrangements. In such cases the body is placed inside the hollow of a large tree with little ritual. It’s thought as the tree grows over the opening its spirit protects and integrates that of the child’s within its own.

Tau tau watch over the village of Lemo from one of many family balconies. The square wooden covers are family vaults housing the skeletal remains of the dead. The freshness of the clothing and the deep tones of the wood on all the effigies suggest they have recently been replaced. Having great value to museums and private collectors, many Tau tau are either stolen or sold off over time.

The moss covered cliffs of Lemo were filled with dozens of family balconies carved at dizzying heights. Most contained between eight and fifteen effigies with dead white eyes staring hauntingly ahead and arms reaching forward. Next to the balconies are the square openings of the family vaults packed with bones and covered with a wooden door. Unfortunately, tau tau have long been considered prized artifacts by private collectors in the West and through the years many of the original effigies have been stolen. Once removed the families often replace the figure, frequently painted and dressed in contemporary fashions as opposed to those consistent with the culture and era of the original ceremony. As such, a rather mixed and matched ensemble of baffling figures emerges over time.

I finished the day with a trip to the village of Londa to visit their internment caves. Toraja of lower rank, lacking the money necessary for a private family cliff side vault, usually place their bones in large communal caves. Pushing through the thick underbrush filled with swarms of oversized ants and other colossal insects I reached the base of the escarpment. Outside the cave large thick wooden containers, vaguely resembling clumsy canoes, were filled with bones and skulls and precariously stacked atop one another. Many of the sides of these “communal coffins” had long since disintegrated in the dankness of the jungle air allowing piles of bones to spill over the spongy ground. No effort had been made to return these loose bones to their original place. Though the Toraja have a deep reverence for the spirits of their ancestors scant sentimentality is wasted on their physical remains. A small platform with several splintered, poorly attired tau tau sat on the ground next to a tiny model tongkonan, obviously left to remind the spirits of their earlier home.

Crouching below a low overhang studded with lichen covered stalactites I entered the mouth of the cave. Inside was piled a massive heap of bones comprising the skeletal remains of perhaps one hundred people, all in various stages of decomposition. Obviously these people carried very little wealth from this world when they died- their families lacking the means to provide either a cliff side vault or a wooden container. A number of the little children who dogged my every step amused themselves by picking up random skulls, holding them in front of their faces and shrieking menacingly trying to scare the visitors or mischievously tapping me on the shoulder with stray femurs. After recording my favorable comments in the village guest book I left.

Later that night, I returned to the singular guest house in town. Under the brilliant starlight of the Torajan night and the deafening roar of insects and animals, I tried to ignore the heavy, stinging scent of the clove cigarettes my house mates smoked in abundance. My reflections on the day’s events were broken by the quiet approach of a solitary gentleman sporting a tall circular black hat customarily worn by Bugi men.

“You went to the villages today?” he asked.

“I did.”

“Would you like to see a buffalo sacrifice?”

“I wasn’t aware there would be any funerals in the near future,” I responded. Truth be known, as a devout animal lover I wasn’t that keen on watching these lovely beasts have their throats slit and their bodies butchered.

“There aren’t any funerals scheduled but for a small contribution I can arrange to have another Torajan ceremony performed where you can see a buffalo sacrifice,” he continued. “Fertility festivals, harvest festivals, the birth of a child, the completion of a new house, all of these can have a buffalo killed.”

Buffalo graze in a traditional funeral ground called a rante. Massive stone projectiles have been placed for each individual whose death has been mourned at this village locale

Apparently a new facet of the Torajan economy had evolved. I knew prior to my arrival funeral ceremonies were not something you could count on seeing. They were basically a hit or miss proposition. However, I’d been told historically buffalo were too valuable a commodity to be slaughtered at anything less auspicious than a funeral. It now appeared the money to be reaped killing buffalo for visitors in staged productions was beginning to tilt the local economic balance in a wholly nontraditional manner. I could just imagine the native garb and feigned ceremony this man could produce for a price. I thanked my new found friend but decided to pass.

Over the next few days I began venturing further afield. Most of the more remote villages were set against the jungle’s edge and fronted by acres of bright green fields under cultivation. They seemed empty of life save a few loose dogs chaperoning me around the area. All the residents could be seen in the distance working in small rice fields, grazing their buffalo, cultivating gardens or harvesting the thick scrub for wood. The tongkonan in these villages were similar to those in the major settlements, though considerably smaller, with less incision under the gables and in need of greater repair. Most were roofed in dull orange sheets of corrugated metal, a reliable modern concession eliminating the need to re-thatch at regular intervals. Though no bones, coffins, vaults or tau tau were seen in many of these smaller, secluded villages, I did occasionally walk across large fields traditionally used to host funerals called rante. Appearing to the uninitiated like any sprawling, open tract, rante are recognizable by large stone formations of conspicuously odd shape set in prominent places. These stone markers function in much the same capacity as tau tau; both being different types of material tribute to the spirits of the local ancestors.

Torajan man in Rontepao. His circular black hat is typical of those who consider themselves of Bugi origin

Finding my way was becoming more problematic as the thickening jungle blocked my lines of sight and the once deep blue veins on my map were gradually fading under the cumulative corrosion of rain and sweat. Clinging to the shadows of a tall stone overhang I slipped out of the forest into a small clearing marking the furthest point of my travels, the village of Suaya. There, hollowed within the rain streaked face of an ascending declivitous rock were three magnificently crafted balconies filled with dozens of aging tau tau. Their once rich, wooden hued bodies, now bleached grey by the elements and barely covered by faded and tattered formal clothing, suggested they were original, unmodified effigies. Their pallor was ghostly, their vision weary yet profound. Time had dulled their expressions and vitality to the extent some could no longer extend their arms. Aging torsos leaned on imaginatively carved stone rails literally sculpted out of the cliff face with great precision as opposed to other, more modern balconies which used bolted pieces of wood to form the railings. At the base of the cliff, suffocating within the determined undergrowth, were miniature replicas of tongkonan and an old wooden carving of a horse.

A young boy seemed the only person noticing my presence. Grabbing my hand he took me down a long path, temporarily disturbing the pleasure of a cluster of large brown snakes sunning themselves in the heat. We were soon joined by his younger sister who was flying a Precambrian sized beetle with a string tied around one leg like a kite. Beneath an enormous tree whose canopy was filled with hundreds of bats stood a large shed with a pale green and black diamond shape on the door. Tugging at the latch, the boy threw open the door to reveal a mountain of thousands of crumbling bones and skulls. We were soon joined by an older villager who spoke passable English. He seemed focused on making sure I was enjoying myself. Telling him how much I liked his village, in particular the tau tau, he appeared surprised. “Those are just old figures, I wanted to change them but nobody would let me,” he said. “Follow me and I will show you newer figures you will like more. Now when people die we do a better job of honoring the ancestors.”

Rounding a turn in the road was a discouraging sight. In the side of a large hill a deep cavity had been dug. Inside the opening were five brand new effigies made of flawless dark brown wood with long braided hair, all wearing brightly colored, flowered shirts, the kind found on Waikiki. Three of the effigies wore sunglasses and two had wooden cigarettes in their mouths. Their platform was painted with green and red stripes and the railing in front was covered in gold foil. They looked like a reggae band taking their bows after a performance. “Aren’t these the best figures you have seen?” he proudly asked. “Go tell all your friends to come to Suaya. Oh, and please remember to sign the guest book.”

I realized I’d just been afforded a glimpse of the future of Tana Toraja and its residents. Like the older tau tau at Suaya, the authenticity and integrity of the traditional Torajan lifestyle seemed to be fraying in the face of the more lucrative enticements of the Western world. Driving the torturous road back to Ujung Pandang I pondered the conundrum of modern existence versus traditional culture. Obviously Torajan culture had been slowly shifting to a more “Western” perspective since 1906 when Dutch colonizers mandated changes in traditional religion, social organization, agriculture and settlement patterns. Most of the Toraja are eager to acquire a greater measure of wealth and security then their historic existence allowed. Who could condemn them for exploiting their cultural resources in an effort to upgrade their standard of living? The concept of isolated peoples living in a natural, idyllic existence, immune to the demands and pressures of modernity obviously appeals to my own romantic notions of the “good life.” However, mine is an opinion formulated from a position of affluence and comfort. How well does it serve those who struggle with the hard edge realities of third world living on a daily basis? Though thrilled to gain a glimpse inside this well preserved existence I fully realized I was witnessing a culture in transition. I was grateful for the degree of traditional authenticity I was privileged to see but wary about what the future might bring.

Since my first visit I have returned to Tana Toraja and seen remarkable change. True to the national master plan the world has enthusiastically embraced the central Sulawesi highlands in heretofore unimagined numbers. Two years after my trip, the road to Rantepao was widened and repaved, literally throwing open the doors to foreign visitors. In 1991, an estimated 215,000 tourists visited the Toraja. In 2002 this figure was estimated to be over 600,000. The influx of tourist dollars has turned Rontepao from a ragged frontier outpost into a spiffy little town with a neat, freshly constructed commercial center filled with retail buildings of appealing design, level asphalt roads with clearly denoted crosswalks and carefully planted and well tended median strips. There is now a new airport to further expedite ease of access and talk of lengthening the runways to handle direct international flights from Europe and other major Asian cities. As of 1993 there were over 30 hotels in the area and travel agencies were beginning to use the internationally recognized “star” system to rate them for comfort conscious tourists. These facilities offer tennis courts, modern business centers and of course the requisite “bamboo bar.” Infrastructure has expanded making electrical and water systems more reliable and all of the inter-village roads are now paved. The town people clearly display a more affluent look in cleaner and more distinctly western clothing. Many Torajans now work in nontraditional crafts. They engage in weaving and metal and wood working to satisfy tourist tastes for “authentic” Torajan cloth, buffalo key rings and tongkonan models for everything from book ends to paper weights. The model village of Kete Kesu is now completely subsidized by the government and is only populated during daylight hours for tourist shows. After dark the former residents return to a newly constructed village down the road.

Most disturbing have been the changes in religious rituals to satisfy tourist tastes. Though I think the Toraja misread the desires of tourists with respect to the appearance of their effigies, perhaps I’m wrong. I’ve not read the totality of remarks within the village guest books. Maybe foreign visitors prefer the tau tau in Hawaiian shirts and tuxedos to their traditional clothing. Unlike me, most tourists now wish to see local rituals conclude with a buffalo slaughter. The practice of sacrificing buffalo is now a routine part of virtually every staged ceremony, not just funerals. So reckless is the practice the area is now finding itself faced with a buffalo shortage. Not wishing to strangle the golden goose, the government has set limits on how many buffalo may be slaughtered during a single ritual and has instituted a buffalo tax for each of the beasts killed. They have also undertaken a program of breeding buffalo for this purpose on the island of Java, though to date with limited success. Regardless of perspective, there is no arguing the Aluk and traditional economy of the area have been radically altered by these new tourist practices. Whether this trade off has been ultimately beneficial to the Toraja remains to be seen. It’s certainly been profitable for the Indonesian government which has rarely been accused of placing the welfare of its indigenous people above its own institutional benefit.

Today the preponderance of anthropological research in the area is focused on assessing the influence of tourism on the Toraja and their traditional way of life. However, anthropologists are in many ways becoming the tools of the commercial expansion of the Toraja. Ethnographers are now avidly courted by village leaders eager to use them as a conduit to the world as they attempt to rewrite traditional culture around their own accomplishments and those of their families. To have an anthropologist in your village now confers a far greater degree of status than any amount of buffalo. Not to be outdone by village egos, the Indonesian government has put their own oar in the revisionist water. In the interest of enhancing tourist perception of the Toraja and their traditional lifestyle, the government has mandated the rewriting and sanitizing of local custom and history along their own lines. Tourism officials feel there to be too much contradiction and confusion, as well as some rather unsavory practices, within the actual cultural character of the Toraja to appeal to emerging tourist interest. Today the government requires all guides to be licensed and to complete a course in the “official” version of Torajan history and mythology. This way a more favorable and uniform presentation may be used to manipulate the Torajan image for optimal commercial effect. Beneath all these conflicting interests the traditional cultural reality is rapidly dissolving.

In many ways the modern world is imposing itself on the Toraja regardless of their desires. Other factors aside from tourism have of late put pressure on the people of central Sulawesi. Starting in 1999, thousands of people in this region have been killed and thousands more displaced in religious violence between Muslims and Christians. Outside provocateurs from the Al-Qaida linked Jemaah Islamiyah have effectively initiated a cycle of sectarian hostilities through the burning of Christian churches and slaughter of rural villagers. Predictably, any protective or stabilizing responses from Jakarta to these acts of aggression have been nonexistent. However, mute on the subject of the Toraja they are not. With a nod to unbridled cynicism and mercenary behavior they have instituted a new tourist campaign headlined by the catchy slogan “Visit Torajaland While Its Culture Is Still Intact.” I number myself among the fortunate few.

Toraja: One of Indonesia’s Most Fascinating and Traditional Ethnic Peoples…

Toraja are an ethnic group who live in districts of Tana Toraja in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Toraja approximately 450,000 live there today. Many Christians and Muslims continue to follow their traditional animistic beliefs and practices. Before the ar…

make money from home ontario

[caption id=attachment_675 align=alignleft width=250 caption=The Torajan village of Kete Kesu outside Rontepao][/caption] The Torajan people on the

how to gain weight fast indian diet

[caption id=attachment_675 align=alignleft width=250 caption=The Torajan village of Kete Kesu outside Rontepao][/caption] The Torajan people on the